The Serve Man

Michael Chambers recounts recent events on Earth after the arrival of a alien space craft. The aliens, known as Kanamit, seem friendly and assure everyone they have nothing to be afraid of. In fact, they offer to share wonderful technology that will provide limitless energy, cure all disease and convert deserts into lush gardens.

The Server Manager Winrm Plug-in

For the people of Earth, paradise has arrived. Chambers is an encryption specialist and they try their best to decrypt a book the Kanamit left behind. The book's title seems benign - but it's not what they think it is. This episode of the Twilight Zone is a must see. Bochner and the supporting actors work naturally in under 25 minutes in this teleplay. The story works on our fears and dreams as the alien Kanamits, all wonderfully played by Richard Kiel, tells the earth that they can turn our war and famined ridden world into a 'Garden of Eden.' The directing and script works so well together that it moves at break neck speed as questions about the Kanamits 'good will' unfolds as you unfold them in your own mind.

“To Serve Man” By Damon Knight The Kanamit were not very pretty, it‟s true. They looked something like pigs and something like people, and that is not an.

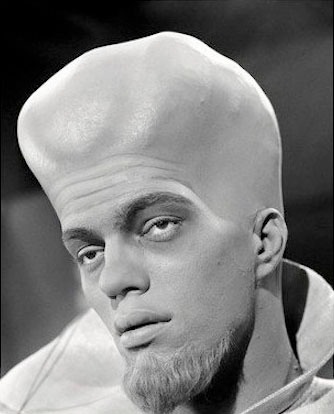

Kiel with bulbous head and darkened eyes doesn't moves his lips as he communicates telepathically. His expressionless face and a tinny Voice Over gives a strange and surreal effect. Good Night Mr.

Vcard to windows contact converter. Windows Contacts is Microsoft's proprietary. Business, Family, and Notes of Contact file into PST, CSV and VCF. Windows Contacts Converter at SoftLay is the right. Convert Contact (.contact) to Vcard..contact to vcard.Contact to vcf Converter free Download convert contact file to csv windows contacts to vcf converter free.

Murder, on the other hand, is up for grabs—and treated with brazen disrespect. On “Hannibal,” corpses are fungible art supplies, like clay or oil paint, in sequences in which bodies are stitched into frescoes or twisted into grotesque displays. Skin is stretched into wings, corpses are bent into apiaries, belladonna is planted in heart cavities. It would be easy to see such choices through a cynical lens, as shock effects: Nietzsche is peachy, but sicker is quicker.

It certainly makes the show a tough one to recommend to strangers. But these images coalesce into metaphors for mortality and loss. A teacup breaks and then comes back together; we see that it’s like a skull shattering, which in turn reflects a grieving man’s wish for time to go backward.

Tears are stirred into Martinis. A woman’s corpse is sewn into a horse’s womb, and after she’s cut out the doctors feel a heartbeat in her torso; they slice her open and a live blackbird flies out. Symbols overlap eerily, as senses do in synesthesia: a heartbeat is a clock tick is a drumbeat. The arch dialogue has the same multiplicity, with ordinary idioms taking on sinister resonance, from “the one that got away” to “the devil you know.” “You smoked me in thyme,” one victim remarks, as he’s served a dish of himself, with typically shrewd double meaning.

In one of last season’s most spectacular scenarios, a black male corpse is discovered in the river, coated in resin. The man had escaped from an art project built by a serial killer Hannibal had never met: he’d torn himself out of a mural comprising dozens of corpses, of varying skin tones—racial diversity reinterpreted as pigment, people reduced to brushstrokes.

When Hannibal climbs a ladder to the top of a corn silo, he looks down and sees a pattern: from above, the curled bodies form an eye. The image suggests outrageous ideas: one eye gazing at another, God at his creation, his creation back at God, through the open pupil of the building’s roof.

Hannibal calls down to the killer, “I love your work.” The scene was so outlandish that it made me laugh out loud. It also felt like a reminder of the show’s own double consciousness about what it means to watch from a distance, to admit that we’re voyeurs who enjoy foie gras and veal. (There are moments when one suspects the show is sponsored by PETA.) For anyone who watches modern television, Hannibal may seem familiar: he’s another middle-aged male genius with a fetish for absolute control, like Don Draper and Walter White and Dr. House and Francis Underwood.

Astrologically speaking, he’s a Sherlock with Lucifer rising. But, mainly, Hannibal suggests the fantasy of the uncompromising television auteur: he’s the perfectionist who cares only that every detail of his vision be realized, no matter what sacrifices that might require.

This is his design. As Season 3 begins, the show has entered a state of feverish theatricality, adding frame upon frame, underlining its own artificiality: in one flashback, Hannibal recites the magic words “Once upon a time,” and a red velvet curtain fills the screen. A fugitive from justice, Hannibal has fled to Europe, where he’s been riding motorcycles, sipping champagne, killing people in order to steal their curatorial positions, and posing as man and wife with his former therapist, Bedelia Du Maurier (the deliciously chilly Gillian Anderson, speaking so low that their scenes are like whisper contests). It’s not entirely clear whether Bedelia is his hostage or his co-conspirator.

“Observe or participate?” he asks, after he bludgeons a man with a bust of Aristotle in front of her. “Are you at this very moment observing or participating?” “Observing,” she whispers, a tear streaking her face. It’s one of many exchanges that seem designed to challenge the viewer’s role but also to suggest that we should stop fooling ourselves.

Bedelia doesn’t hurt anyone, but she is too curious to look away. Like anyone who can’t stop watching Hannibal, she’s decided that what he offers is too good not to have a taste. ♦.